The True Myth of Dune Part Two: The Baptismal Journey of the Hero (Part I)

How the messianic pattern of Myth is transforming Paul Atreides through death into life.

The sand against his skin is scalding to the touch, but Paul leans into it instead of flinching away. It is comforting. Even the oppressive heat of the day is a solace to him, which somehow only seems to be climbing instead of waning as the Hand of God passes before the sun's face. The eerie shadow of the eclipse enhances the crushing weight of that heat, making it difficult to even breathe. Paul still embraces it. It validates the emotions resonating within him. The heat matches his rage. The searing pain matches his grief. Arrakis is smoldering, burning, and radiating – like his heart.

Sister. Father is dead. Shouldn't you go back to the stars, be with him? Paul prays silently to the throbbing womb of this world. In his mind's eye he can see his sister’s angelic, embryonic form floating like a gossamer into the cooling, gentle arms of the Void. She should, at least, be allowed to be free. I'm afraid I won't have enough time to fix things before your coming. This world is beyond cruelty. Even though Paul has finally found sanctuary with the strength of the Fremen people, the fact that it hadn’t been by the side of his Father, Gurney Halleck, Duncan Idaho – is a corrosive poison to his bones and fuel to the flames of grief burning his insides. Now he is all that remains of a noble house, Paul Atreides, the Duke's son, against an insurmountable and terrible enemy, to protect family, honor, friends, and now seitch.

Well, not entirely alone. There’s his mother’s religion, her belief that wove his very genes into being. That path frightens him more than anything, that birthright that keeps pulling at him like the weight of a collapsing star which threatens to consume all things. Mother Mohaim’s voice haunts him: Because you are Jessica’s son. Paul knows exactly what it means to be Lady Jessica's son. That kind of power is so hateful to him not because it repulses him, but because it completes him. It feels right. It feels like a second skin. How absurdly cruel, that no matter how much he would resist, this Power will win. And when it does Paul will be gone and only the Kwisatz Haderach will remain.

Yet he also remembers the Voice: Don’t be frightened. Even a little desert mouse can survive. . .

“What do you call the little desert mouse that jumps?”

With Hollywood churning out franchises, biopics, and remakes and the looming horror of AI slowly poisoning our culture, there exists a beautiful cinematic oasis and respite in Villeneuve’s Dune trilogy. The unfolding of story with heart and power the likes of which we have not seen since perhaps Lord of the Rings has swept the world with an unquenchable fire, with Dune Part One and Dune Part Two breaking records in the box office and charming the minds and hearts of audiences globally. Sand, spice, water, worms – Dune taps into the primeval and spiritual aspects of our human experience in a way that feeds the soul like a man thirsting in the desert finding water. Like how Lady Jessica clinging to her son after her experience with the worm’s poison, the Water of Life, urges him to “Behold the beauty and the horror!” So too Villeneuve urges us to behold these things in his films.

The fulfillment of a young filmmaker’s dream, Denis Villeneuve has brought to life Frank Herbert’s acclaimed science fiction series, books that were near and dear to his heart. This is a labor of love for Villeneuve, and you can just tell how much of himself he has poured into this series. My focus is primarily on the film's themes and symbolism, but I could write countless articles on the art and craft of these films alone. I would highly recommend reading the Art and Soul of Dune books, which go in depth of the phenomenal, nigh impossible feats of cinematic magic that take my breath away just reading about them.

Needless to say, ‘Dune Era’ has been an experience like no other, and for me personally it has been a profound shift in how I experience cinema and story and has ignited and baptized my imagination like nothing else. It is for this reason that I desire to tap into this phenomenon and outline precisely why Villeneuve’s Dune affects us and speaks to us in the way that it does. It is not an arbitrary thing, this event, or simply a coincidence. These films are tapping into “old magic,” I would say, a storytelling tradition that is so deeply infused into our culture’s storytelling and image-making, that we have long sense forgotten its existence. It had a name once: The True Myth.

The ‘The True Myth’ is something British author and theologian C.S. Lewis coined when discussing the intersection of Myth and Reality, of religious experience with knowledge; namely and significantly the ‘Christian Myth’ with human history. “The heart of Christianity is a myth which is also a fact. The old myth of the Dying God, without ceasing to by myth, comes down from heaven of legend and imagination to the earth of history. [...] We pass from a Balder or an Osiris, dying nobody knows when or where, to a historical Person crucified (it is all in order) under Pontius Pilate. By becoming fact, it does not cease to be myth: that is the miracle.” (Lewis 66-67).

Within this understanding from Lewis, we can see that the myths and stories that Mankind has told himself since time immemorial aren’t made up in the sense that we moderns conceive of as delusions, e.g. the belief of lies over truth, the imaginary over fact, but that imagination and fact are in actuality unified and synthesized. To hold both together is not to diminish one or the other, but it is precisely this union that brings us closest to experiencing Truth, and not just knowing Truth. “If God chooses to be mythopoeic – and is not the sky itself a myth – shall we refuse to be mythopathic? For this is the marriage of heaven and earth: Perfect Myth and Perfect Fact...” (Lewis 67).

It is in the mythopoeic that stories like Dune can open to us truths that also delight the soul. Mythopoesis being not just story-making, a literary discipline, but where the abstract and the literal abide together. It is the liminal space where God comes down to commune with Man. It is only us moderns who struggle with this notion of the Divine communing with the Human. We separate Myth and History and view them as opposing and conflicting concepts. The ancients would not have struggled with this understanding or even made these distinctions. “The blowing wind was not like someone breathing – it was the breath of God.” (Johnson 4) In this same way, Myth is not like Truth, but is infused with it, made from the substance of it. “We make still by the law in which we’re made.” (Tolkien line 71). It is through the act of Myth-making (storytelling) that we call into existence that which was already innate within Creation. The imagination of Man is not his own invention but is divinely inspired and originates from God. Therefore, all myths and stories reflect Truth.

This multidimensional understanding of Truth means that Myth can grow “for different recipients in different ages” through ever varying meanings. It is not that everything becomes Truth, but that Truth inhabits everything, and therefore Story becomes a means by which we encounter God, and in doing so we are inevitably transformed to some degree. Story is transformational. Man’s encountering of Myth is a transfiguring force. “And we all, with unveiled face, beholding the glory of the Lord, are being transformed into the same image from one degree of glory to another.”

So, Paul Atreides is walking a path that many heroes have gone before him, but with a very specific twist that I believe makes his story truest to this nature of mythopoesis. From the very beginning when Paul discovers on that fateful night in his encounter with the Gom Jabbar that his mother specifically birthed him to be “the One,” the Kwisatz Haderach, Paul has struggled against his identity and purpose. Where most heroes embrace the journey of the chosen one narrative, Paul Atreides, at every point is actively fighting against it. He is moving upstream from the Myth. Paul is refusing to enter into his own story but is instead being compelled by it along the way. Paul is wrestling with the Divine, and by doing so Dune reveals the painful, but crucial intersection of suffering and transformation within the Divine Image. That to pass from one world to the next, which is how we can understand transformation, there must first, by necessity, come Death, an unraveling and dissipating, for there to be Life, revelation and renewal. “Paul Atreides must die for Kwisatz Haderach to rise.”

At first glance, we might find this counterintuitive, even backwards, to think of one moving forward in this fashion. It is an upside-down inside-out kind of thinking where we are used to the traditional hero’s narrative having a more straightforward trajectory, from humble beginnings to glorious ends. This is why many interpret Paul Atreides’ story as being a villain's narrative, a fall from grace trajectory that goes from innocence to corruption, light to darkness. However, if we view Paul’s story as such, it flattens the whole narrative thematically. This is not because a villain’s narrative is not mythopoeic, but because of what it does to Paul’s story specifically, which Villeneuve has intentionally structured.

For example, where we see this upside-down structuring of the narrative most clearly in the first film is with Paul’s relationship with Dr. Liet Kynes, the Judge of the Change, who is also Fremen. At their first meeting, Paul has a bit of the hero’s naivety. He is just being himself - brilliant, intuitive, and understanding Fremen ways instinctively. However, by doing so, Paul becomes part of the Myth without realizing it, something that affects even one such as the inscrutable Kynes. When they next meet, he has passed through the fire and lost nearly everything. He is now wary, discerning, and distrusting, as he tries to understand Kynes’ motives and intentions in helping them when she had been ordered “to say nothing, to see nothing.” Here Paul realizes that, paradoxically, the Myth is becoming his only option if he wants any semblance of agency and power. In their final interaction at the ecology station, Paul intentionally puts on his role of Lisan al Gaib to this end, taking on the Myth despite himself. “I’ve seen your dream.” The Myth, which is abhorrent to Paul, is the only path open to him.

This relationship with Kynes represents the Fremen allegorically, and how Paul’s eventual relationship with them will be like, which finds its ultimate cumulation and manifestation in Dune Part Two, beginning with the Fremen War Council scene when Paul declares himself the Lisan al Gaib who will “lead them to Paradise” to the end when the fire of the Holy War fully ignites and the Fremen are unleashed in violent zeal upon the Great Houses. “A great man doesn’t seek to lead, he is called to it. And he answers. I found my own way to it. Maybe you’ll find yours.” Paul is finding his own way through the Myth, and it is hurting him like hell.

This tension with the Myth arises from the modern assumption that for something to be Good, it cannot have Absolute Power. “What your people have done to this world is heartbreaking,” Paul accuses his mother, the Bene Gesserit now turned Reverend Mother. When she tries to justify that it was done to give people hope, Paul bellows in rage, “That’s not hope!” Not only is the mythic narrative surrounding him shown as inherently dangerous in its control and manipulation of people, but Paul is also terrified of what the religious zealotry surrounding his own legend will bring into the world. His visions that haunt him in both waking and sleeping show only horror and death. This power that flows in his veins is a curse, something he despises. Even when things begin to get desperate for our heroes with the siege of Sietch Tabr and the call for all leaders to rally together in the South, Paul still refuses to go because of the mantle of that messianic power which awaits him there. He is terrified of this power not because he loses control, but because he gains it; a God-like authority that inevitably will lead to the terrors of the Holy War.

This cautionary approach to the hero’s journey and the power of its own myth is not without merit. Myth is dangerous. It isn’t something that can be taken as a little thing. It reminds me of the conversation in C.S. Lewis’s The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe regarding Aslan, the Great Lion, the God-being of Narnia. Susan remarks on whether this Lion is safe to be around or not. The idea of Aslan being a creature, something other and therefore unpredictable, makes her nervous. Mr. Beaver responds, “Who said anything about safe? 'Course he isn't safe [...] He's the King, I tell you.” By its nature, the Myth, and those whose being is constructed of its supernatural substance, would necessarily have to be unsafe. Any supernatural power is inherently uncontrollable, uncontainable, and unknowable by human might.

Yet as Mr. Beaver also reminded Susan about Aslan, “But he's good.” Just because the Myth is dangerous and can be terrible beyond imagining, does not make it any less beautiful or any less good. It doesn’t make it any less good for us.

That's why Paul Atreides as villain strips the narrative of significance because it doesn’t transform the audience in its telling. It makes only one assumption and then predictably follows that line of argument without any challenge to said assumption. However, if we interpret Paul’s journey through the mythopoeic hero’s journey which flows from the pattern of the Messianic, then Paul’s relationship with the Kwisatz Haderach and the future it holds for him as Ruler of the Imperium is meant to open our eyes to something deeper. It is describing to us what happens to the human heart when it encounters the Myth. It is describing the nature of transformation within a person who encounters the Divine! - As I have been using both terms almost interchangeably. Paul’s journey unfolds between worlds where the Myth is chaffing against him like a refiner’s tool but is also a part of him closer than his breath. This is what it truly means for Paul to be the Lisan al Gaib, the Voice of the Outer World. It is not about whether others should believe he is the Messiah or follow him as the Messiah, but what does the Messiah in him reveal of him? Like a Dante-esque journey of passing through Hell first to reach Paradise, this upside-down cosmology of Paul’s Messianic path is leading him to a specific kind of divine revelation, a revelation that transfigures.

Like Jonah’s disobedience which lead him through the belly of the whale and the sea, like Job’s testing through loss and suffering that lead him to see His God, or like Jacob who wrestled with the Angel all night long until he was made lame but given a new name, Paul’s struggle with the mantle of Lisan al Gaib and the suffering because of his legend will transform him in the same way. He will be baptized into death in order that he may be reborn into life – passing from the world of the old into the world of the new.

Just because the Myth is dangerous and can be terrible beyond imagining, does not make it any less beautiful or any less good. It doesn’t make it any less good for us.

Therefore, in the manner of Dante, who passed through the “Nine Circles of Hell” in The Divine Comedy, I’m going to be taking a cue from this storytelling cosmology and utilize my own term, The Circles of the Amtal. I believe Villeneuve has intuitively structured his films within these concentric thresholds where Paul is passing from death to life each time. In my previous analysis, Walking with God: The Sacred Journey of Villeneuve’s Dune, I pointed out this concentric narrative structure in Dune Part One. The Amtal, we learned, was the idea of knowing a thing well, of knowing its limits. “Only when pushed beyond its tolerances will true nature be seen.” I showed how the final Amtal between Jamis and Paul and Paul’s test with the Gom Jabbar were one in the same. “He wields our power. He had to be tested to the limits.” Now, in Dune Part Two Villeneuve is continuing in this pattern, as the story picks up only a few hours from when we left off in Part One.

For the sake of time, I will be limiting my focus to just three circles, the ones I feel are the most critical to the story, e.g. Paul drinking the Water of Life, Paul before the Fremen War Council, and the fight between Paul and Feyd-Rautha in the Imperial Tent. However, from the opening sequence of the eclipse on Arrakis to the moment the emperor kisses Paul’s ring, these circles and their corresponding visual cues are operating. I would keep this in mind as we follow Paul into the upside-down and the inside-out.

Paul Drinks

“The visions are clear now. I see possible futures. All at once. Our enemies are all around us. And in so many futures, they prevail; but I do see a way. There is a narrow way through.”

“For the gate is narrow and the way is hard that leads to life, and those who find it are few.” | Matthew 7:14

When Paul’s mother drinks the Worm’s poison and has her eyes opened, Paul is faced with a terrible choice. “You must do what I did. You must drink the Water of Life,” mother urges son with a frenzied and cloying madness. Passing from the regal and respected Lady Jessica of House Atreides to Reverend Mother of the Fremen, a holy witch who walks around muttering under her breath to her unborn child, the Water of Life is a mechanism of transformation. Does it obliterate or does it renew? “Drink and you shall die. Drink and you may see. . .” is the ritual promise (or curse) of that terrible liquid. The different fractions of Fremen argue over its substance, one side thinking it nothing more than “worm piss” and the other a sacred liquid that connects them to their ancestors and to the world of prophecy. Regardless of these tensions that pull and tug at Paul, it seems as if his cup is chosen for him. When the Harkonnens go on the offensive under the leadership of Feyd-Rautha, who lays waste by raining fire upon sietch and stone, all the voices around Paul urge him to go South. He must go South and regroup with all the Fremen tribes. However, that is where the Maker’s Temple lies, that desert well of the Water of Life. If Paul goes South, he knows what awaits him there: death.

“A good hunter seeks the highest point. You need to see,” the words of friend Jamis urge him gently and clearly. When Paul seeks his friend’s advice, we are given a distinct visual cue, Paul’s hand reaches out to touch the heart of Arrakis. It connects this moment with the moment in Dune Part One, just before Paul fights with Jamis, when he was told that he would have to follow his path unto death there as well. In the first film, Paul’s hand is adorned with his father’s ducal signet, and here it is not, but its absence signifies Paul’s struggle against his destiny. Earlier in the film, Paul had removed the signet ring because he had believed he had “found his way.” By putting away the ring, Paul believes he can make his own destiny and that he has no need to wield his power and authority. Ironically, this comes just after Paul has chosen his war name “Maud’Dib” “the one who points the way,” Paul’s right hand and his father’s signet are operating under the same symbolism. So, right at this moment, as Paul seeks his friend’s advice, we are shown this image of his right hand. We recognize what is happening. Paul is entering the Myth. He is stepping into the Messianic pattern, the power of the Kwisatz Haderach.

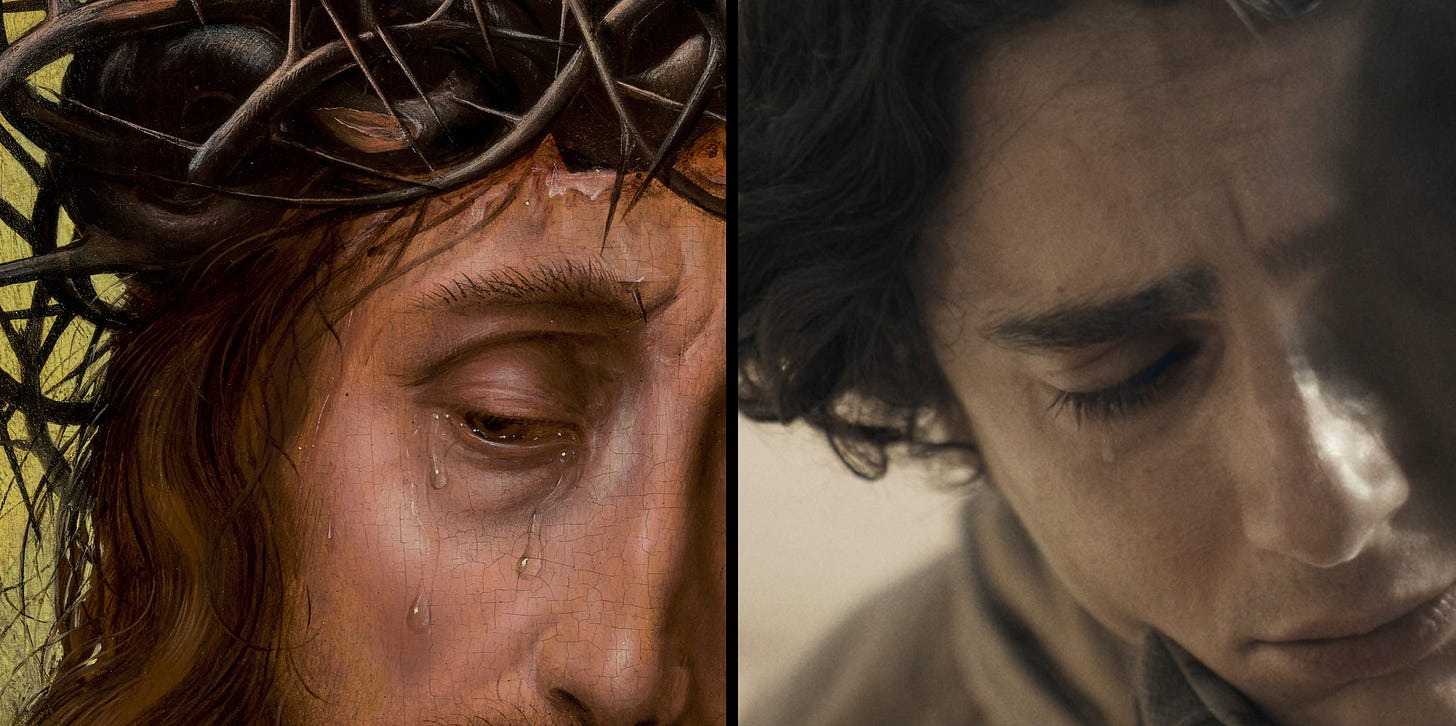

So, like Christ enduring the agony in the Garden of Gethsemane, sweating blood, asked of His Father, “…if you are willing, remove this cup from me…” so to Paul comes before Jamis (who functions symbolically as the Divine) to ask if there is another way. “Speak to me, Jamis,” he urges in anguish. Yet it is not Paul’s will that is to be done, but the will of the one who forms the path for his feet: the Myth. “Then I will do what must be done,” is Paul’s resigned statement spoken through streaming tears of holy agony. He has been handed this cup, and so he must drink.

“Are you able to drink the cup that I drink, or to be baptized with the baptism with which I am baptized?” | Mark 10:38.

When Paul passes into the South, steps in the Maker’s Temple, and drinks that cup that waits for him there, he is baptized into death. As I have stated before, this isn’t a death that leads to annihilation, but something greater. Paul is walking the enflamed and purifying pattern of Palm Sunday and embracing his Death and Resurrection in order that the Myth can strip and peel away with the lacerating precision of whips and thorns, that which is no longer needed for what lies ahead for him. As Paul’s sister speaks to him once he drinks, “Oh, brother, my dearest brother, you are not prepared for what is to come.” And what is it that Paul is not prepared for? To his horror, he discovers that he is Harkonnen! His enemy, the enemy of his family, the very people who have destroyed everything he loved most, are a part of him. He has been given eyes to see into his own heart and found his enemy there. “You need to see. . .”

Paul, then, concludes, that to achieve his goal of destroying them he must embrace his Harkonnen identity. He must become them. The Myth is drawing this out of him, like fire bringing impurities to the surface. It is his pride, cruelty, and hatred. It is the Harkonnen in Paul that is being burned away. Paul is being sanctified through the suffering of the mythopoeic path. “Although he was a son, he learned obedience through what he suffered.” We see that the hero’s obedience to the journey is for this singular purpose, namely the fruit of righteousness. “For the moment all discipline seems painful rather than pleasant, but later it yields the peaceful fruit of righteousness to those who have been trained by it.” This is what it truly means for Paul to pass through the Narrow Way. And we must remember that this journey is not over yet. “My road leads into the desert. I can see it.”

Paul is being sanctified through the suffering of the mythopoeic path. We see that the hero’s obedience to the journey is for this singular purpose, namely the fruit of righteousness.

Southern Messiah

“The Hand of God be my witness! I am the Voice from the Outer World! I will lead you to Paradise!”

“But Jacob said, ‘I will not let you go unless you bless me.’” | Genesis 32:26

With Paul having passed the threshold between life and death in more ways than one, he has finally succumbed to the full power of the Kwisatz Haderach and the mantle of the Fremen Messiah. Wading through the “corridor of anger” amidst hundreds of thousands of the Fremen and storming into the Assembly Chamber, he establishes himself as Lisan al Gaib, his voice thundering like damnation before the people (Lapointe pg. 196). “I’m pointing the way!” He roars when Stilgar and the others dare to challenge his authority to speak. Although Paul walks this path, again, he continues to move against its current. His flurry of emotions are not only directed at his enemy, but at the Myth that compels him to claim power he has never wanted. Each circle that Paul passes through strips closer and closer to his heart, to the marrow of his soul. Paul is fighting for his life. “Do not resist,” the Voice keeps telling him throughout his visions. But he resists. Even when he is forced to choose the Myth, he resists! And the Myth pushes back, like iron against iron, like the hammer against the smoldering hot metal, Paul is cut, slammed, crushed, burned, and bent into place. Each hammer blow is fashioning him, molding home, and remaking him. Even his own words are like fire burning his throat as he speaks them, the Myth turning him inside out, breaking him apart from the inside, dissolving him.

We can see this unfolding as Paul stands on the stone mound of the Assembly Chamber. The Fremen teeter on the edge of the knife, horrified that an outsider dares to challenge them and their sacred customs and yet all of them are there precisely for this fulfillment of prophecy. With a voice that could melt hearts and sear souls, Paul uses the Kwisatz Haderach to proclaim the ancient name of Arrakis: Dune. I can’t help but draw comparison to when the last time we heard a character call Arrakis by this name. It was by the Baron himself. “My desert. My Arrakis. My Dune.” Paul, like the Baron, is claiming ownership and possession through his naming. This is the Harkonnen in Paul continuing to manifest.

However, naming a thing has power within itself. To name a thing is to create it. It is a God-like trait. To name a thing is to bring it into existence. “Let there be Light…” and we know there was Light. And Adam, made in God’s image, did the same. “Now out of the ground the LORD God had formed every beast of the field and every bird of the heavens and brought them to the man to see what he would call them. And whatever the man called every living creature, that was its name.” Paul has been infused with this God-like authority, and here instead of using it for the holy purpose it was meant for, he instead is using it as a means of manipulation for his own gain. He is stirring the Fremen heart to war. So, if naming in its intended and righteous form is meant for creation, then naming in its corrupted form can only be doing one thing: decreating. It is an undoing, a destructive force that unravels the very nature and identity of things. Paul is actively unmaking the Fremen identity before their very eyes! Yet, as I said, Paul’s words, the power of Myth, is doing the same thing to him. “When you take a life, you take your own.” Paul is unmade by his own words through the unmaking of the Fremen!

Yet when Paul cries out to the “Hand of God” with his own raised hand, an act of defiance against the violent and brutal destruction that radiates out of him, through him, and around him from his ascendancy as Lisan al Gaib, he is also desperately holding onto life. “This is my father’s ducal signet,” Paul declares. “I’m Paul Atreides Duke of Arrakis!” The image of the signet ring is unfolding its deeper meaning of Paul’s destiny and his immutable spirit. It shows that the fiery, destructive force that flows from out of him, the Myth turning him inside out, is also revealing the parts of Paul’s soul that are indestructible. He will die, but not be destroyed — Paul’s unyielding spirit striving with the dreadful scouring of the Myth and prevailing. For even as he is being sloughed away, skin to bone, cut through to the very marrow of his soul, Paul cannot let go of breathing and living, he must walk this path that was laid out for him through the desert. “I will not let go unless you bless me!” This is Man and Myth wrestling in a relentless, endless confrontation of wills. Man and Divine meeting and striving face to bald face. What will the result be of such a bitter, bold, and glorifying wrestling between God and Man, His created child in His image?

“Your name shall no longer be called Jacob, but Israel, for you have striven with God and with men, and have prevailed.” | Genesis 32:28

That is the beauty of the mythopoeic path, that it brings us deeper and deeper into the theophanic experience with the Truth. As we follow Paul through his tribulation of the Calvary road into the desert, we will continue to learn precisely what it means for the Myth to be indwelling and how this relates to the idea of the “God-man,” namely the Incarnation. Of course, we won’t see the full manifestation of this until Villeneuve’s Dune Messiah, but I believe Dune Part Two still has more for us to glean in this regard, giving us hints at what is to come. I hope you join me for Part II of The Baptismal Journey of the Hero in Villeneuve’s Dune.

Works Cited:

Johnson, Kirstin Jeffrey. Rooted in all its Story, More is Meant than Meets the Ear: A Study of the Relational and Revelational Nature of George MacDonald’s Mythopoeic Art. 2010. University of St. Andrews, PhD. thesis.

Lapointe, Tanya, with Stefanie Broos. The Art and Soul of Dune Part Two. 2024.

Lewis, C.S. God in the Dock. 1970.

Metsys, Quentin. Christ as the Man of Sorrows. (Netherlandish, 1465 or 1466 - 1530). Getty.edu. https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/109P8R

Tolkien, J.R.R. Mythopoeia. https://www.tolkien.ro/text/JRR%20Tolkien%20-%20Mythopoeia.pdf Accessed June 15, 2024.

I would pass all day long on reading those articles 💯